Shall I Compare Thee to a Polarity Score? Sentiment Analysis of Shakespeare’s Sonnets

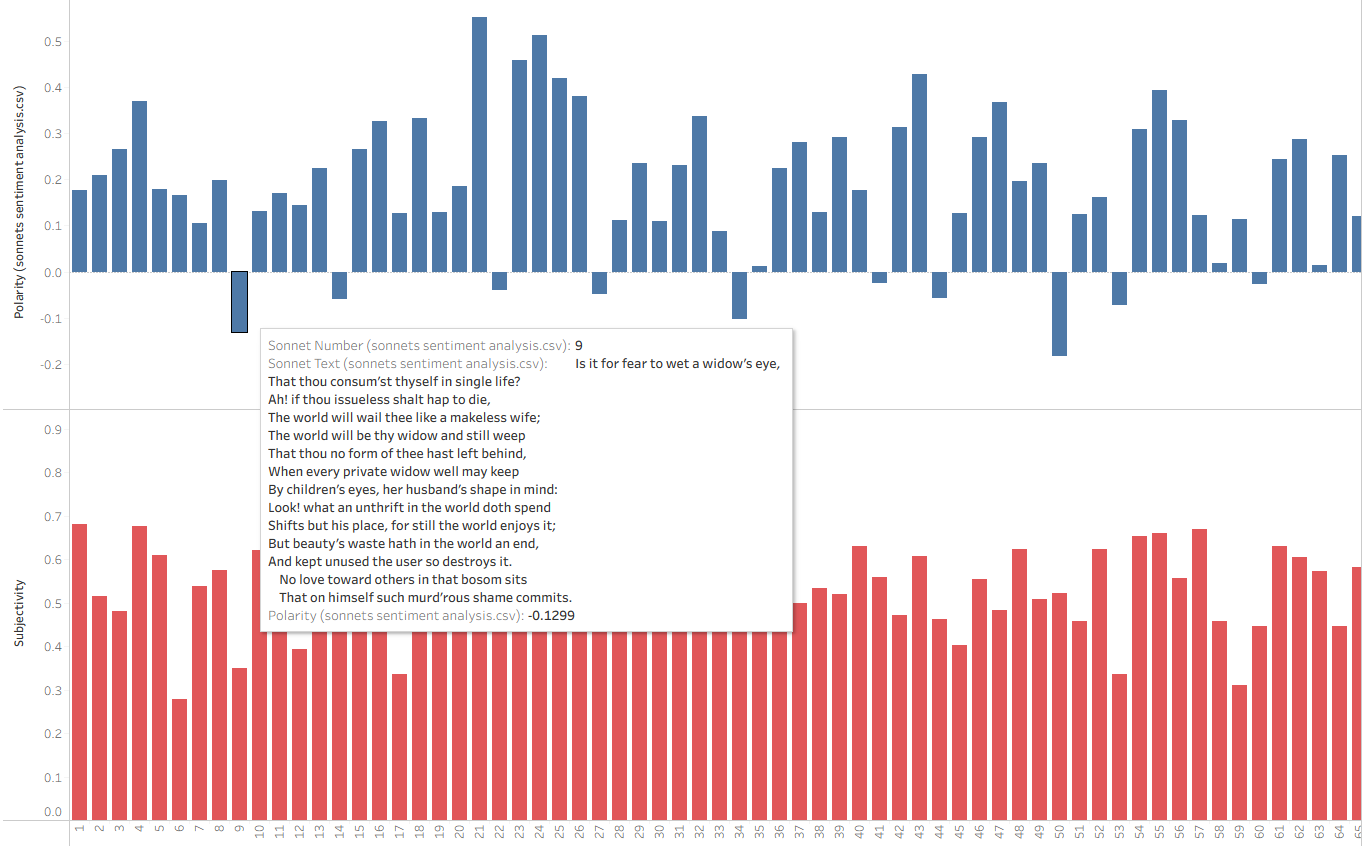

While building a Tableau Dashboard to explore Shakespeare’s sonnets, I became curious about how modern sentiment analysis tools would handle Renaissance language. The conclusion was exactly as expected: not particularly well.

However, the process served as an excellent case study in text processing. By using TextBlob to calculate polarity (positive/negative tone) and subjectivity (opinion/fact), I was able to build a framework that could easily be reapplied to more modern datasets, such as Amazon or movie reviews.

Compiling the Sonnets

I started with the Project Gutenberg version of the sonnets. To transform a raw text file into a structured CSV with sonnet numbers and text, I had to build a custom parser. A unique challenge here was that Gutenberg identifies sonnets with Roman numerals, which I needed to convert to Arabic numerals for better data handling.

My approach involved creating a helper function for the numeral conversion, then iterating through the file line-by-line to identify headers and group the subsequent text. After drafting the initial logic, I used Claude to refine the code and make the parser more robust against formatting inconsistencies.

import csv

import re

import os

def roman_to_int(roman):

//Roman Numeral Conversion Helper

roman_map = {'I': 1, 'V': 5, 'X': 10, 'L': 50, 'C': 100, 'D': 500, 'M': 1000}

total = 0

prev_value = 0

for char in reversed(roman.upper()):

value = roman_map.get(char, 0)

if value < prev_value:

total -= value

else:

total += value

prev_value = value

return total

def sonnet_parser(input_path, output_path):

roman_pattern = re.compile(r'^\s*([IVXLCDM]+)\s*$')

sonnets = []

current_number_str = ""

current_lines = []

if not os.path.exists(input_path):

//include error checking when opening text file

print(f"Error: Could not find '{input_path}' in {os.getcwd()}")

return

with open(input_path, 'r', encoding='utf-8') as f:

lines = f.readlines()

for i, line in enumerate(lines):

match = roman_pattern.match(line)

if match:

# If already collecting a sonnet, save it

if current_number_str and current_lines:

arabic_num = roman_to_int(current_number_str)

sonnet_text = "\n".join(current_lines).strip()

sonnets.append([arabic_num, sonnet_text])

# Start new sonnet

current_number_str = match.group(1)

current_lines = []

else:

if current_number_str:

current_lines.append(line.rstrip())

# Final sonnet grouping

if current_number_str and current_lines:

sonnets.append([roman_to_int(current_number_str), "\n".join(current_lines).strip()])

# Saving to CSV

with open(output_path, 'w', newline='', encoding='utf-8') as f:

writer = csv.writer(f, quoting=csv.QUOTE_ALL)

writer.writerow(['Sonnet Number', 'Sonnet Text'])

writer.writerows(sonnets)```Analyzing with TextBlob

With the data formatted, I turned to the TextBlob library. TextBlob offers a straightforward API for common Natural Language Processing (NLP) tasks, specifically providing a polarity score (-1, 1) for positive/negative emotional weight and a subjectivity score (0, 1) for determining fact vs. opinion.

Admittedly, 16th-century sonnets are not the primary use case for this library. A truly accurate Shakespearean analysis would require a custom weighting scale to account for the specific emotional gravity of metaphors like "winter," "sickness," or "burning." Furthermore, many sonnets are steeped in sarcasm or emotional ambiguity that even literary scholars debate.

Despite these limitations, the results offer a fascinating comparison between human interpretation and algorithmic "best guesses." TextBlob makes this data incredibly accessible:

#define my functions for polarity and subjectivity

def get_polarity(text):

return TextBlob(text).sentiment.polarity

def get_subjectivity(text):

return TextBlob(text).sentiment.subjectivity

#Run on the text column of my datafram

df['Polarity'] = df['Text'].apply(get_polarity)

df['Subjectivity'] = df['Text'].apply(get_subjectivity)

From Shakespeare to The Beatles

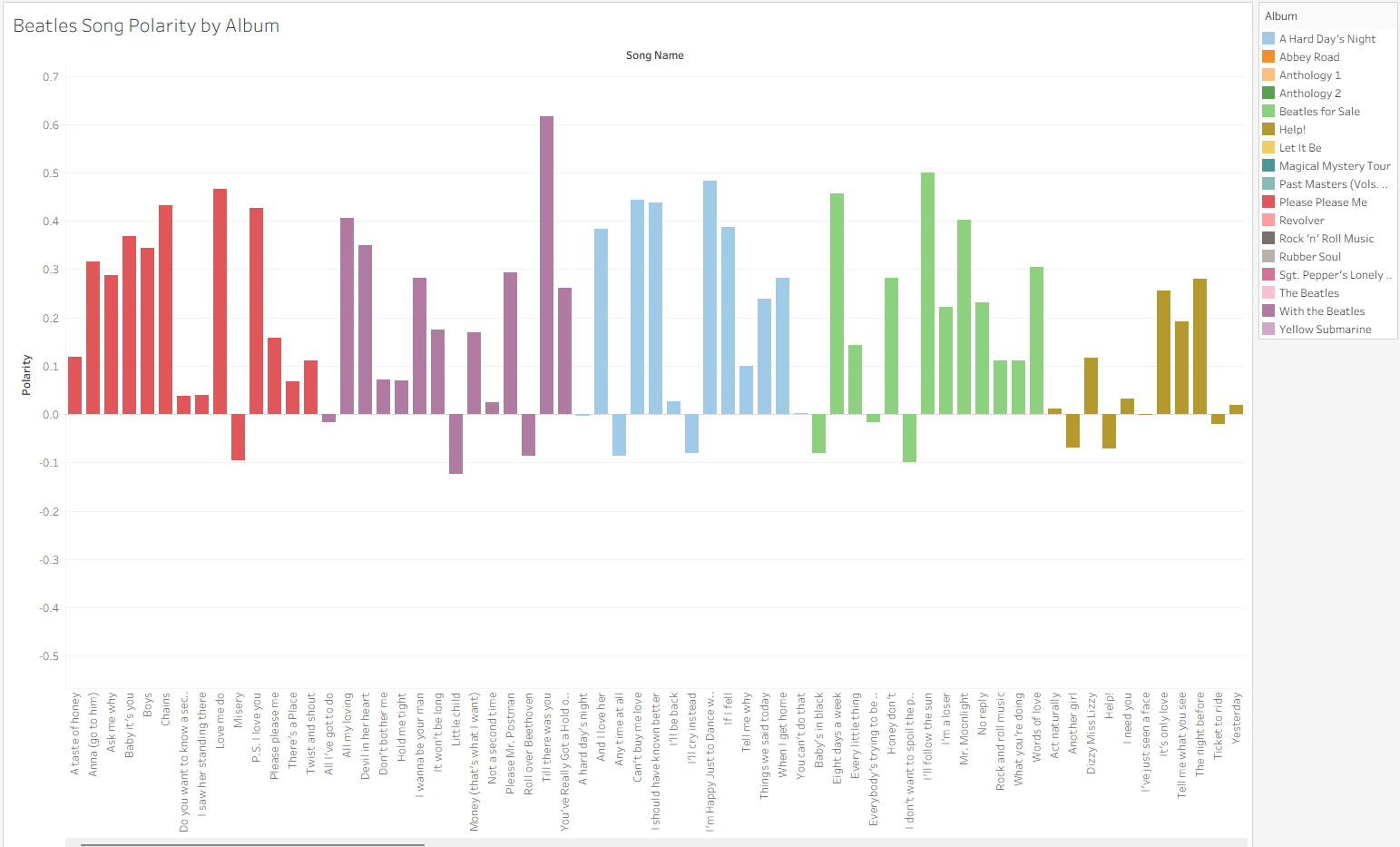

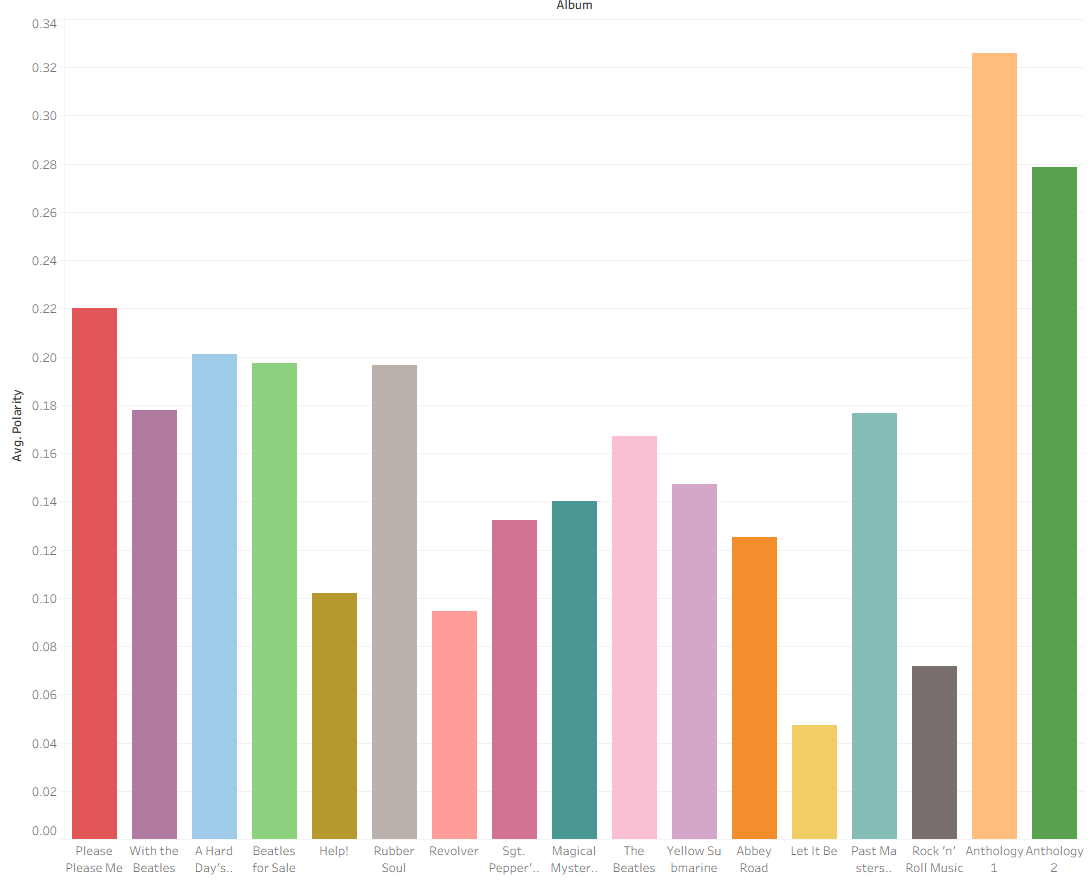

Interestingly, applying this same logic to The Beatles' discography felt much more aligned with expectations. Modern song lyrics, while still poetic, are closer to the linguistic patterns these models are trained on.

Analyzing The Beatles allowed me to explore aggregate sentiment across entire albums. Having recently read Ian Leslie’s John & Paul: A Love Story in Songs, I’ve been thinking about the emotional weight behind their catalog. Using sentiment analysis to augment the study of songwriting—from the Bard to the Fab Four—opens up significant opportunities within the Digital Humanities.

While this project was an artistic exploration, the practical applications are clear: businesses can use these same workflows to analyze posts, customer feedback or reviews, gaining quantitative insights from massive amounts of text data in seconds.

Stay tuned for my upcoming Tableau visualizations based on these datasets!